|

|||||

People of the Forestby Charlie Round-TurnerEVERY SUMMER, thousands of pilgrims stream into the temple complex at Kataragama, in the southeast corner of Sri Lanka, joining a fortnight-long annual festival where Buddhists (most of the majority Sinhalese), Hindus (most Tamils), Muslims, and other groups celebrate and worship together — an example of how harmoniously the Sri Lankan people can co-exist.

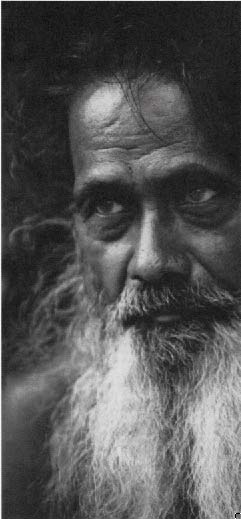

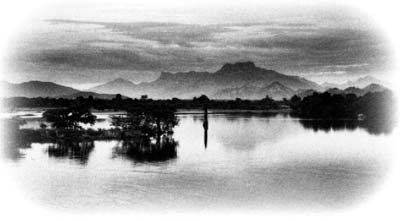

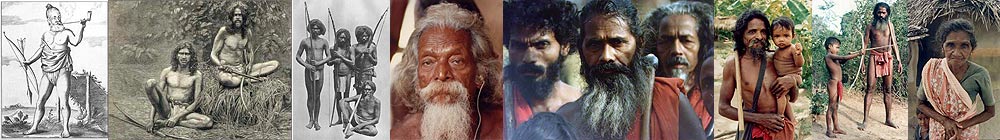

This image is at odds with the twenty-year record of bloody conflict between the Tamil Tigers and the predominantly Sinhalese government. Promisingly, the two groups are slowly working through a peace process, begun with a ceasefire agreement in February 2002. Now of course, Sri Lanka is occupied with the even greater task of healing broken hearts and communities after the recent tsunami disaster. Hopefully, the two groups will work together in a spirit of cooperation, perhaps further lessening old antagonisms. However, there is still an important group of people whose human rights have yet to be fully recognised — Sri Lanka's indigenous Wanniya-laeto (People of the Forest), also known as the Veddha. Archaeological evidence suggests their Neolithic ancestors inhabited this island 10,000 years ago or more. By contrast, the first Sinhalese came over from India around the sixth century BC and the first Tamils about the third century BC. During the Twentieth Century, in a tragic echo of native peoples in other parts of the world, the Wanniya-laeto were persuaded to give up their hunting and gathering lifestyle and integrate with the (largely unsuitable) mainstream agricultural economy. They were given little choice anyway. Huge expanses of the land they had been natural caretakers of for thousands of years were turned into national parks and reserves, most of which they are now forbidden to enter. Some still follow the traditional way of life — and many more want to — but they have used only campaigns, not violence, to appeal for justice. Others are willingly or reluctantly adopting the mainstream Sinhalese culture and way of life — along with problems such as alcoholism, a common side effect of such unsuccessful social assimilation. The basic right of self-determination should be reason enough to give them justice. However, as with many other such groups around the world, they have valuable knowledge to offer modern society; clues to the development of ancient cultures, indigenous philosophy, knowledge of the local ecology, and more. Two members of the Wanniya-laeto visited the United Nations in Geneva in 1996. Uru Warige Wanniya, now the leader of the Wanniya-laeto, addressed the Working Group on Indigenous People (UNWPIP), which in turn sent a strong appeal to the Sri Lankan government to honour the rights of the Wanniya-laeto. There have been some words of promise and minor concessions, but effectively little has changed. In 1998, the government officially allowed the Wanniya-laeto the right to hunt in certain areas, but they still risk being shot by wardens if they enter the reserves — let alone hunt. Meanwhile, illegal poaching and logging continues, often condoned by corrupt officials. Sustainable eco-tourism is the buzzword in Sri Lanka now, but the unjust treatment of the Wanniya-laeto blocks progress towards an enlightened environmental and human rights accord. I first saw the Wanniya-laeto at the Kataragama Festival, in August 2003. Here, their precedence and importance in Sri Lankan history and culture is acknowledged and they have an honoured role in the ceremonies. Dressed in red sarongs, each with an axe hooked over his shoulder, long bearded and wild haired, they are the epitome of proud, fierce warriors. However, when I was introduced to Unapana Kallua, he cheerfully invited me to stay with them at Dambana near Maduru Oya National Park. I was only able to spend two days with them, yet their warmth and the pleasure they showed in simply sitting around talking and laughing impressed me deeply, particularlygiven the difficulties facing their society. One afternoon some of the men took me for a walk into the forest. After an hour, we emerged from the trees by the shore of a reservoir, more an idyllic lake in appearance. A single fisherman slowly poled his boat in the centre, jagged hills formed a scenic backdrop, fish eagles and pelicans cruised overhead. Walking along the edge of the water, the men suddenly detoured into the bush. We soon came across a large fallen tree. I could see nothing remarkable until they pointed out a small hole. Two bees crawled out — a beehive, the second they had found that afternoon. As they widened the hole with a machete,

Temporarily sustained by fresh honey, we marched back to their cottage for a more reviving snack of tea and fruit. "Butakanda, ne," Kallua lamented. ("No elephants"). They had hoped to show me elephants in the wild, which would have been a more appropriate setting than the tourist safari I had been on a few days earlier. Yet it had been inspiring simply to roam this remarkable landscape with the Wanniya-laeto, truly the People of the Forest. Courtesy: Kyoto Journal Vol. 63 CHARLIE ROUND-TURNER is a freelance writer and photographer based in the UK. |

| Living Heritage Trust ©2024 All Rights Reserved |